WELCOME TO THE GOOD LIFE

One thing that makes philosophers unique among academics is

just how often, and how fervently, they defend the importance of the subject.

Almost every university has a ‘Why study philosophy?’ page, selling the subject

to potential undergrads. Very few universities, as far as I’m aware, have a

‘Why study biology?’ page. The first question seems to require answering in a

way that the second doesn’t.

So whenever some celebrity-scientist questions the point of

philosophy, you get one-hundred furious responses from philosophers arguing for

the importance and even urgency of tackling philosophical

problems. Philosophical reflection, they tell us, is vital.

"As far as I’m concerned philosophy is the most important subject of all because other subjects get their importance by how they relate to the larger issues. And that’s what philosophy is about – the larger issues."

– John Searle, New Philosopher

"When someone asks 'what’s the use of philosophy?' the reply must be aggressive, since the question tries to be ironic and caustic. Philosophy does not serve the State or the Church, who have other concerns. It serves no established power. The use of philosophy is to sadden. A philosophy that saddens no one, that annoys no one, is not a philosophy. It is useful for harming stupidity, for turning stupidity into something shameful. Its only use is the exposure of all forms of baseness of thought. Is there any discipline apart from philosophy that sets out to criticise all mystifications, whatever their source and aim, to expose all the fictions without which reactive forces would not prevail?"

– Gilles Deleuze, Nietzsche and Philosophy

I’m not so convinced. Contrary to what I wrote in my

personal statement, I’ve never lost sleep over a philosophical problem.

Sceptical doubts have never kept me up at night. The problem of induction has

never left me tossing and turning. I don’t believe, like Socrates, that the

unexamined life is not worth living. I don’t believe, like Camus, that we need philosophy to hold us back from suicide. The vast majority of it I see as a game, a project,

as good a subject as any to spend three years on.

Because, honestly, what’s the harm if we never work out how

atoms in the brain combine to create subjective experience? What’s the harm if

we never prove we’re not all dreaming right now? It’s true that some people are

worried about these problems – perhaps you’ve worried about them yourself – but

these worries aren’t urgent. After all, they can only be sustained by a

deliberate effort. If you find yourself on the verge of a crisis, try the David Hume manoeuvre. Put the book down, have some dinner and play some backgammon:

"Most fortunately it happens, that since reason is incapable

of dispelling these clouds, nature herself suffices to that purpose, and cures

me of this philosophical melancholy and delirium... I dine, I play a game of back-gammon, I

converse, and am merry with my friends; and when after three or four hour's

amusement, I wou'd return to these speculations, they appear so cold, and

strain'd, and ridiculous, that I cannot find in my heart to enter into them any

farther."

– David Hume, A Treatise of Human Nature

For me, philosophy is only urgent if it’s about living well. If it doesn’t relate to that, it’s not important. It

might be fun – and it often is – but it’s not important.

As far as living well goes, two parts of philosophy are

immediately relevant. The first is axiology. This is the part that asks,

‘What’s valuable?’. The second is ethics. This is the part that asks, ‘How

should I behave?’. The two are closely related, such that your answer to the

first question can’t help but inform your answer to the second, and vice versa.

Both play key roles in answering a third question, ‘What does it mean to live

well?’

And this makes ethics and axiology something that so much of

philosophy fails to be: practical, useful, relevant

to everyday life. Your ethic and your axiology are not just things you

write about in a book or speak about at a lecture, they are things you live every

minute of every day, through every dream you have and every decision you make.

Every time you say thank you, make someone a cup of tea, or pee in the pool,

you’re deciding how to behave. You’re living an ethic. Every

time you meet up with friends, go for a run, or decide to have one more drink,

you’re deciding what’s valuable. You’re living an axiology.

Given this, it’s no exaggeration to say that ethics and

axiology are the most practical subjects you can study. Whether you realise it

or not, you’ve been doing them your entire life, and whether you like it or

not, you’re going to continue doing them until the day you die. You've got to value something, and it's all to easy to get hooked on the wrong things. I think it’s

important then – urgent even – to give some thought to what it means

to live well. There are, quite literally, lives at stake.

So what does it mean to live the good life?

This was another of the six or seven songs that I cycled

through on YouTube as I was just getting into Kanye and it might be my favourite of

the lot. The beginning – the way it jumps straight in with T-Pain and the synths –

carries the promise of an obstacle overcome, a goal achieved, a destination

reached. It’s as if by the very fact of listening you’ve been invited into the

good life and it’s going to be all champagne and roses from here ‘til eternity.

Or at least for the next four minutes.

But, of course, the first step in reaching the good life is

determining what the good life is, and the jury’s still out on this one.

There are three main theories about what makes a good life:

hedonism, desire-fulfilment theory and objective list theory.

Hedonists say

that the good life is the life of pleasure. They claim that pleasure is the

only thing that makes your life better and pain the only thing that makes it

worse.

Desire-fulfilment theorists say the good life is the life where you get

what you want. They claim that having your desires satisfied is the only thing

that makes your life better and having your desires frustrated is the only

thing that makes it worse.

Objective list theorists say the good life is not so

simple. They claim that lots of different things can make your life go better

(for instance, pleasure, desire-satisfaction, acting morally, achieving things,

having friends, being in love) and that missing out on these things makes your

life go worse.

HEDONISM

A lot of people are unconvinced by hedonism. Claiming that

all that matters in life is pleasure seems juvenile and shallow. The word

brings to mind images of people with smiles pasted on but little behind the

eyes, always chasing that next hit of dopamine.

This is unfortunate because it’s not what hedonism is about.

The word is one of many in philosophy whose meaning has been distorted by

newspaper columnists keen to flaunt their slapdash acquaintance with

intellectual history (see also ‘existential,’ ‘solipsistic’, and, most outrageously,

‘epistemological’ and ‘ontological.’).

Hedonism is about all kinds of pleasure, not just sex, drugs

and rock ‘n’ roll. In fact, it’s less misleading to say that hedonism is about

pleasant experiences, because even the word ‘pleasure’ makes it seem more

sordid than it is. Far from getting loose and living for the weekend, the

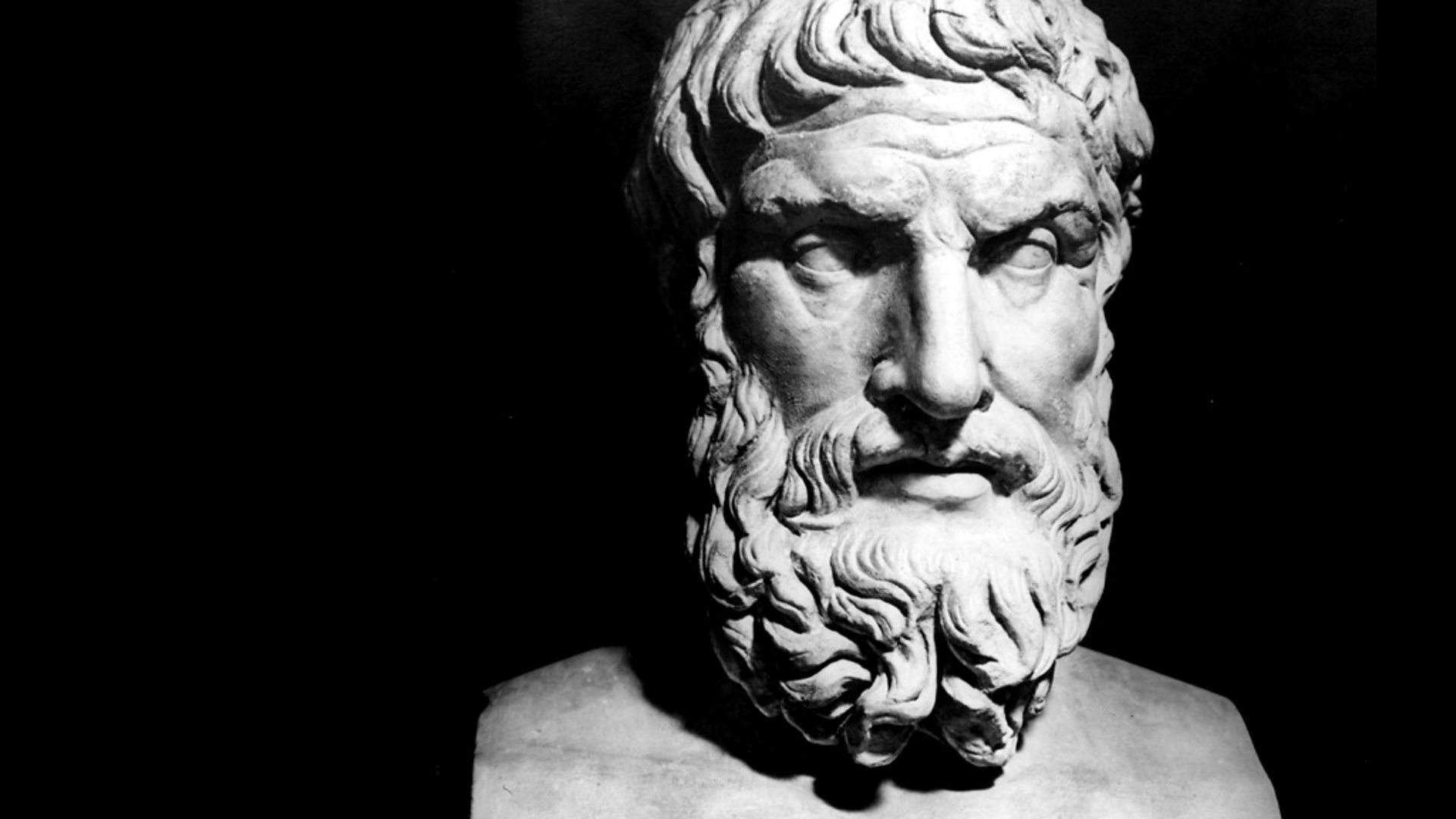

most famous hedonist, Epicurus, spent his days gardening, meditating and

conversing with friends. He wouldn’t even eat fine foods because he thought

that craving them would lead to more pain in the long run, so he stuck to

water, bread, olives and occasionally cheese.

|

| Not a big party guy. |

But there are other objections to hedonism. The most famous

is Robert Nozick’s experience machine:

“Suppose there were an experience machine that would give

you any experience you desired. Superduper neuropsychologists could stimulate

your brain so that you would think and feel you were writing a great novel, or

making a friend, or reading an interesting book. All the time you would be

floating in a tank, with electrodes attached to your brain. Should you plug

into this machine for life, preprogramming your life’s experiences?”

– Robert Nozick, Anarchy, State and Utopia

Most readers answer no to this question. Even though life in

the experience machine could be set up to be extremely pleasurable, they’d

still to prefer to live in the real world. This seems to indicate that pleasure

alone is not enough for a good life. We need other things too, like contact

with reality. So, Nozick says, hedonism is false.

A lot of philosophers take this passage to be a knockout

blow. As far as they’re concerned, Nozick is Rocky at the end of Rocky IV and

hedonism is Ivan Drago, out-cold and face down on the mat, never to fight

again.

I’m not so convinced. We ought to note that not everyone has

the same intuitions about the experience machine. Some people say they would

enter (you might even be one of them). And I think that, of the people who say

they wouldn’t enter, fear plays a role. Status-quo bias – an irrational

preference for avoiding the unknown and sticking with things you know – is a

real thing and I think it might be at work in the experience machine case. Thus

conclude my few words in defence of hedonism, and if you don’t like them I

have five and a half thousand more.

DESIRE-FULFILMENT THEORIES

The second main theory of what makes a good life is

desire-fulfilment theory. This is the one that says getting what you want is

the only thing that makes your life better and not getting what you want is the

only thing that makes your life worse. Here, again, though, we need to be

careful to avoid misunderstanding. The ‘fulfilment’ in 'desire-fulfilment’ must

be understood in the logical sense, not the feeling sense. This means that your

desire is ‘fulfilled’ if what you want to happen actually happens, regardless

of whether or not you feel fulfilled or whether you even know it’s happened.

This clarification is important because it makes the theory

subject to an objection from Derek Parfit: the stranger on the train example.

“Suppose that I meet a stranger who has what is believed to

be a fatal disease. My sympathy is aroused, and I strongly want this stranger to

be cured. We never meet again. Later, unknown to me, this stranger is

cured. On the Unrestricted Desire-Fulfilment Theory, this event is good

for me, and makes my life go better. This is not plausible. We should

reject this theory.”

– Derek Parfit, Reasons and Persons

Parfit was never a man to mince words. And I agree that this

theory should be rejected. It just doesn’t seem plausible to say that the

stranger’s recovery makes your life go better. His life? Sure.

Your life? No.

The reason it doesn’t make your life go better is because it

doesn’t really concern you at all. Once you’ve forgotten about the stranger,

his recovery isn’t in any way connected with your life. In order to avoid the

stranger-on-the-train objection, desire-fulfilment theorists need to restrict

their theory to discount desires about things that are too remote.

Thus, we have the success theory, which says that only

desires about your own life count: only their fulfilment makes your life go

better. Now there’s a minor technical problem with this theory: it’s difficult

to draw a clean line between desires about your own life and desires not about

your own life. For instance, is your desire that your siblings are successful

about your own life? Probably. After all, you spent a lot of your life

interacting with them. Is your desire that your second cousins are successful

about your own life? That’s not so certain.

But we’re not going to focus on that because the success

theory faces a more pressing objection, again from Parfit. Call it the drugged-up objection:

I know that you believe the success theory. That is, I know

that you believe having your desires about your life fulfilled makes your life

go better. So, I say, I’m about to make your life amazing. I’m going to inject

you with a drug that is extremely addictive. Every morning from now on, you’re

going to wake up with an overwhelming desire to have another hit of this drug.

Your desire itself won’t be painful, but if you don’t get an injection within

an hour you’ll start sweating and twitching. That’s okay, though, because I’m

going to be there every morning with that needle you so desperately crave. The

effects of the drug are neither pleasant nor painful, but they keep your

desires at bay until the next morning.

On the success theory as it stands, this arrangement would

significantly improve your life. You’re getting intense desires about your life

fulfilled every morning. That means your racking up some serious points on the

success-scale. But our intuition tells us that this is not a good life. So, the

argument goes, the success theory must be false.

But desire-fulfilment theories aren’t dead yet. Without

wanting to make a load of pasty pedants seem too heroic, philosophy often feels

like Hercules fighting the Hydra and this case is no different. The latest head

of desire-fulfilment theory is the global success theory. This theory is just

like the success theory except that instead of adding up individual desires to

determine how well your life is going, it counts only desires about your life

as a whole. In response to the addiction objection, the global success theorist

can say that being addicted does not make your life go better because your

overall desire, knowing all the facts, is not to be addicted.

But we’ve got one more objection to consider, this time from

John Rawls. Call it the grass-counter objection:

Imagine a high-flying, young Harvard professor. She’s

incredibly talented and looks set to solve some famous problems in mathematics.

She also happens to be a great writer and public speaker. She could write a

best-selling book, to rave reviews that include phrases like “illuminating,”

“enchanting,” and “underlying poetry.” She could deliver a TED talk that would

have audiences resonating with the Riemann hypothesis on not merely an

intellectual level but an emotional level.

She chooses to do none of these things. She recognises that

she could, but instead decides to quit her job and spend her days counting the

blades of grass on the Harvard lawns.

The global success theory has to say that the grass-counting

life is better for her than the life of glitz, glamour and Gaussian

elimination. The grass-counting life fulfils her global desires – it’s what she

wants to do. But, we might object, the math life is obviously better, so the global

success theory is false.

This objection is by no means a knockout. A lot of people

are happy to say that the grass-counting life is better for

her. What side you come down on seems to be largely a matter of individual

feeling, and it’s difficult to give reasons for your choice that will convince

the other side. If you think you’ve got a good reason for preferring one life

over the other, let me know. You might just make a major axiological

breakthrough.

OBJECTIVE LIST THEORIES

The final theory about what makes a good life is objective

list theory. Objective list theorists are those people who always accuse you of

being overly reductive and lacking nuance. They say the good life can’t be

reduced to one element as hedonists and desire-fulfilment theorists allege. In

reality, you need lots of stuff for a good life, like pleasure, achievement,

friendship, morality, and love.

Now this sounds all well and good. It’s the

kind of commencement-address-philosophy that goes down a treat with people who

like their wisdom in list-form. But as a general rule in philosophy, we should

be suspicious of any theory that includes a list of more than two elements.

Usually it’s a sign that things aren’t as simple as they could be.

I think the rule serves us well here. If we’re suspicious of

these extra elements – achievement, friendship, morality, love, etc. – we’ll

ask ‘Why do these things make our lives go better?’ And I think, in

every case, we’ll answer, ‘Because they bring us pleasure’ or ‘Because we

desire them.’ In this way, objective list theorists turn out to be either

secret hedonists or secret desire-fulfilment theorists. They agree that the

only thing that makes a good life is either pleasure or getting what you want.

They’ve just given us a helpful list of things that are pleasurable and

desirable (the nice way of putting it) or they’re suckers for a list and have

failed to ask an important question (the mean way of putting it).

Now it’s important to note that objective list

theorists will not be happy with the way I’ve presented things here. They claim

that the stuff on their list makes our lives better even if they

aren’t pleasurable and even if we don’t want them. In order to

try convince you of this, they might say something like:

‘Imagine you have a choice between two lives. In Life A, you

spend your almost all of your time sitting on the couch watching old Seinfeld reruns

and eating Jaffa Cakes. In Life B, you work hard and become a world-famous

athlete, the first person to run a marathon in less than two hours. You

experience exactly the same amount of pleasure in both lives. Which life would

you rather live?’

Chances are you're going to choose Life B. Then when you do, they’ll say, ‘Aha! That means

that achievement makes your life better even if it doesn’t bring you more

pleasure! So objective list theory is true!’

I don’t buy this. I think the reason we think that Life B

is better is because, despite the stipulation, we can’t help but think that Life

B would be more pleasurable. When considering examples of this kind, we must

remember that (1) our minds often work by association (think of the pleasure

that normally follows your achievements and the shame that normally follows

day-long sitcom binges) and (2) our minds are naturally reluctant to respect

stipulations (think of that little voice in your head that whispers ‘But the

ton of bricks must be heavier than the ton of feathers.

They’re bricks.’).

To stop this achievement-pleasure association distorting the

way we see the example, let’s imagine an achievement that wouldn’t bring pride

or pleasure. So, for instance, if you’ve ever been to an American mall you

might have come across a car-kissing competition. In these competitions, a

brand-new car is parked in the middle of a mall and contestants have to kiss it

for as long as they can. They get a ten-minute break each hour but otherwise

have to keep puckered up until they can’t take it any more. I’ve found a few

news articles online about these kinds of competitions and note that Kara Stone

reportedly kissed a car for seventy hours back in 2012. That’s almost three

days. What’s more, she wasn’t the only person to do this. Patricia Emery took

her right down to the wire! In the end they had to put a stop to it and decide

the winner on a coin toss. Imagine spending three days expressing your undying

devotion to a car and having it wrenched away from you on a coin toss.

So here’s our new example:

‘Imagine you have a choice between two lives. In Life A, you

spend almost all of your time sitting on the couch watching old Seinfeld reruns

and eating Jaffa Cakes. In Life B, you spend almost all of your life, with the

exception of hourly ten-minute breaks, kissing a car. You are not participating

in any competitions, so you win no cars. You are kissing the car purely because

doing so is an achievement. When curious passersby ask why you do it, you

reply, with as much conviction as a car-kisser can muster, ‘Because it’s

there.’ You experience exactly the same amount of pleasure in both lives. Which

life would you rather live?’

What do you reckon? If you’re now indifferent as to which

life you live, then you don’t believe achievement in and of itself makes your

life go better. You might very well be a hedonist. If you’d still rather be the

achiever than the sitcom-watcher, you’re probably an objective list theorist.

If you decide that you’re an objective list theorist, your

work is just beginning. You now have to decide what things make it onto your

list. I’ve already mentioned a few candidates but all kinds of things

have been proposed over the years. Here are a few to get you started: pleasure,

desire-fulfilment, achievement, morality, love, friendship, knowledge,

creativity, appreciation of beauty, spirituality, religion, wealth, power, and compassion. Circle a few

and ask yourself if these things would still make your life better even if they

weren’t pleasurable or desirable. If they would, then you’ve got a list-item.

Thus concludes our whistle-stop tour of the good life.

Congratulations if you managed to sort yourself into one camp. Double

congratulations if you sorted yourself into a camp and discovered that you’re

living a pretty good life already. Commiserations if you can’t decide which

kind of life is best. If it’s any consolation, you’d probably make a good

philosopher.